I last discussed the discourse with a woman from Samaria. This will continue this week’s summary about the initial ministry with early events during Jesus’s first tour of Galilee. As before, we’ll be referring a lot to places identified on this map of the region:

And for reference, here’s the list of events covered in this week’s readings:

Discourse in the Nazareth synagogue

Call of disciples in Capernaum/Bethsaida

Discourse in the Capernaum synagogue

Exorcism in the Capernaum synagogue

Healing of Simon’s mother-in-law

Tour of other Galilean synagogues

Healing of a paralyzed man in Capernaum

Discourse with disciples of John at the lakeside of Gennesaret

Discourse about the Sabbath in corn fields near Lake Gennesaret

Healing of a man with a withered hand in the Capernaum synagogue

Crowds gather near Capernaum/Bethsaida

Discourse in the Nazareth Synagogue

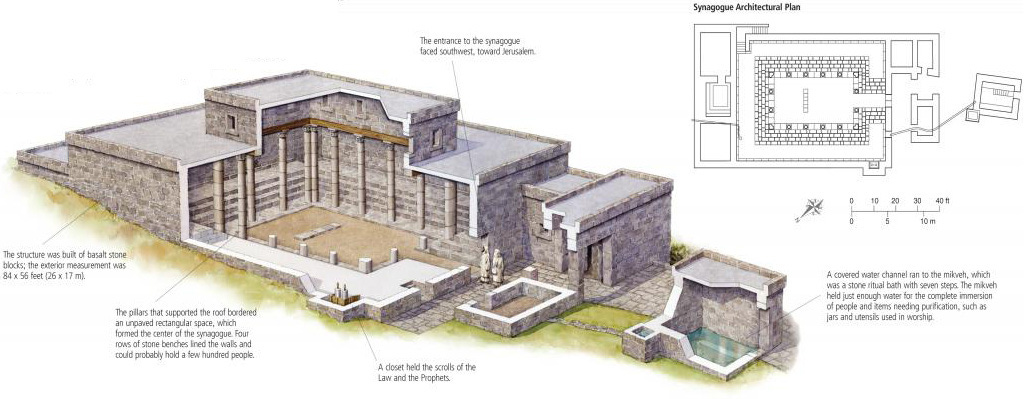

In class, we examined this graphic from the ESV Study Bible that gives a rendering of the Gamla Synagogue, a structure excavated in the late 1970s at Gamla, a village about 45 miles from Nazareth. The Gamla Synagogue structure is the earliest synagogue to have been discovered in Judaea to date—and the only building that can be identified with certainty as a synagogue from the Galilee-Golan region before the year 70 AD—so it represents an important window into the synagogue culture at the time of Jesus. We can imagine the synagogue at Nazareth looking quite similar to that of Gamla’s.

The term “synagogue” is Greek (συναγωγή/synagōgē), meaning most literally, “assembling” or “collection.” (Syn = “together” + agō = “to bring”.) Remember that Jewish people in the 300s BC experienced a Hasmonean (Greek) occupation before the later Roman (Latin) occupation, and so their common language shifted from Hebrew to Greek. The synagogue of Greek-speaking Jews in North Africa referred to both a local Jewish community and its central building. By Jesus’s time, this institution had spread to virtually all of the Jewish communities that survived imperial occupations.

Temple vs. Synagogue

We can sense the gravity of the temple as we read about Jerusalem and the long shadow it cast over Jewish life at the time. But we can’t forget how the synagogue replaced the temple as the central religious institution in Jewish life—the temple, as Jesus lamented, had become elitist and available only to a select few, whereas the synagogue revitalized Jewish culture among the masses in the face of imperial opposition and helped Jewish people resist total cultural assimilation.

Synagogue leadership mattered for events in Jesus’s life, as we will see. Village elders running the local synagogue functioned as local magistrates, and the Roman government was content to let them manage local matters. This meant for Jewish people, the Torah served as the legal basis for most policy decisions and for resolving civic disputes. Village elders rendered legal decisions in synagogues, something to which Jesus referred when he told disciples, “they will deliver you up to councils and flog you in their synagogues.” The synagogue building had a dual function as a place of worship and as a civic hall, leaving it open to everyone, Jewish people and Gentiles alike. The temple, however, restricted access to Jewish priests and certain patrons; a “Women’s Court” restricted even Jewish women to a side area, preventing women from witnessing Israelite or Priestly Courts, and non-Jews were prohibited entry. (When the Roman emperor Caligula demanded a statue of himself be placed inside the temple in the year 40 AD, Jews revolted.)

A wide range of activities occurred inside synagogue campuses. On the Sabbath, attendees participated in scriptural readings, communal prayers, hymn singing, sermons, targum (recitations of Hebrew scripture but translated into common languages), and piyyut (chants or songs of liturgical poems). Whereas temple rituals were often conducted privately in silence and emphasized quiet reverence, synagogue worship was vocal and public. One of Jesus’s innovations (that deeply irked the Sadducees and chief priests of the Jerusalem Temple) was to convert the temple into a synagogue: at the moment he cleansed the temple, he invited commoners into its spaces that had been reserved for priests and began teaching them, much like he did in the synagogues. The mixed company of men and women in Jesus’s audience frightened the chief priests enough that they avoided punishing him on the spot.

Jesus in His Hometown Synagogue

We know Jesus grew up in Nazareth at least since the time his parents relocated there after their escape to Egypt during Jesus’s infancy, and we can reasonably estimate the population of the village at that time to around 20 to 40 (extended) families, or around 300 to 600 residents. (Something like one of our wards.) It’s safe to assume Jesus knew just about every villager in Nazareth and that they knew him. Luke says it was Jesus’s custom to attend the synagogue on the Sabbath, so we can also safely assume Jesus participated regularly in synagogue life—meaning, further, that he could have taken a turn in village leadership. Because synagogue elders spoke of Jesus as “the tekton” (“carpenter” in the KJV; “artisan/craftsman/handyman” in most ancient Greek texts), he may have never served in village leadership but rather kept a trade until his ministry. In any event, Jesus’s presence in the Nazareth synagogue is not noteworthy at this moment in his initial ministry, but rather routine.

The Gamla structure suggests attendees sat on steps along the perimeter of the main hall while an attendant brought scrolls to a table at the center. Sabbath meetings often followed a liturgy, meaning, a rote sequence of worship activities:

Torah reading. (Assemblies typically completed a reading cycle of the Torah in 3–3.5 years.)

Haftarah, or Nevi’im reading. (Nevi’im = “the Prophets,” a collection of prophetic texts that became part of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament.)

Instruction.

Sermon(s).

Targum recitation.

Communal prayer.

We can assume the Sabbath assembly Jesus attended on this occasion followed the typical liturgy, and that the gospels note Jesus’s actions rather than narrate the whole meeting. So, for context, let’s imagine the scene: the Nazareth synagogue convenes with attendees sitting in the round/perimeter while a leader and scroll attendant place Torah scrolls on the center table. The leader begins reading from Torah in its Hebrew form, regardless of those in the audience who know or don’t know the Hebrew language. Then he sits down. Perhaps someone stands, indicating they would like to read from the Nevi’im scrolls; perhaps Jesus is the first to stand, but in any event, at some point Jesus stands, and the attendant brings the scroll to him. We don’t know if Jesus selected the passage of Isaiah in the scroll, or if the synagogue read the Nevi’im in a cycle like they did with the Torah and Jesus happened to pick up their reading at this particular passage. Either way, still standing, Jesus reads from the scroll, again in Hebrew, what appears today as Isaiah 61:1–2:

רוּחַ אֲדֹנָי יְהוִה, עָלָי–יַעַן מָשַׁח יְהוָה

אֹתִי לְבַשֵּׂר עֲנָוִים, שְׁלָחַנִי לַחֲבֹשׁ

לְנִשְׁבְּרֵי-לֵב, לִקְרֹא לִשְׁבוּיִם דְּרוֹר,

וְלַאֲסוּרִים פְּקַח-קוֹחַ

לִקְרֹא שְׁנַת-רָצוֹן לַיהוָה, וְיוֹם נָקָם

Ruakh adonai adonai, alai-ya’an mashakh adonai

Othi levasser anavim, shelakhani lakhavosh

Lenishbere-lev, liqro lishvuyim deror,

Val’asurim peqakh-qoakh

Liqro shenath-ratson ladonai, veyom naqam

The LORD’s spirit is upon me,

as the LORD has anointed me, to bring good tidings to the poor,

to bind up the broken-hearted, to proclaim freedom to the captives,

to the prisoners, release

to proclaim a year of favor for the LORD

Jesus then closes the scroll and gives it back to the attendant who walks back to the table with it. Jesus sits, and the assembly anticipates the next part of typical Sabbath worship—for Jesus to give instruction about what he just read. Those in the audience who know Hebrew (probably only a few) can recognize the words; those who don’t know Hebrew (probably most, since they all speak Aramaic) can recognize the sounds of poetry in this reading, and may even recognize this as a famous Isaiah passage. To this point, these audience members and Jewish people at large understood this passage from Isaiah to be referring to Isaiah himself—in other words, not as a prophecy of a Messiah. (Christians much later will associate this part of Isaiah as Messianic prophecies because of how they interpreted what Jesus says about it in the Nazareth synagogue; but in this moment, this is simply a statement by Isaiah affirming how God had called Isaiah to bring good tidings to the poor and to bind up the broken-hearted and proclaim freedom and a favorable year of the Lord.)

Jesus begins his instruction saying, “Today this passage is fulfilled in your hearing.” The synoptics suggest that Jesus offered more instruction but don’t give us the words themselves. After Jesus discusses, apparently, how Isaiah’s words had been fulfilled, the audience wonders aloud about the teachings, calling them “marvelous” and “gracious,” “speaking well of him [Jesus],” and then wondering how their own fellow villager had become so erudite. “Is this the same handyman we’ve known? Is this same son of Mary?” they ask each other. I might paraphrase the reaction this way as well: “How did Jesus get so smart? Where did he learn all these fancy interpretations?” We don’t have from the text, actually, any suggestion yet that Jesus identified himself as Messiah. Contextually, it’s far more likely that Jesus’s instructions about Isaiah have stirred their surprise. He seems quite different to them than the handyman they’ve known, a real scribe or Rabbi in his own right.

What shifts the reactions comes next. Jesus responds to their shock and awe by saying, “You will surely tell me this parable: ‘Physician, heal yourself!’ Whatever we have heard take place in Capernaum, do here in your hometown also!” We can imagine this reply sparking a different reaction—Jesus is suggesting that he will do more than give smart instruction at synagogue, and that his neighbors in Nazareth will someday press him to perform those feats among them. But, he predicts, he won’t.

As I try to imagine the scene in the regular speech patterns of the time, I might render what comes next like this. Jesus continues, “Truly, I’m telling you, there were many widows in Israel in the days of Elijah when it didn’t rain for three and a half years and a great famine was over all the land, and Elijah was sent to none of them, but only to a widow woman in Zarephath out in Sidon. And there were many lepers in Israel in the time of Elisha, and none of them was made clean except Naaman the Syrian.”

Jesus’s audience can hear what Jesus is implying: Jesus won’t come back to Nazareth and won’t perform any kind of feat or miracle; what’s more, Jesus just associated himself with Elijah and Elisha. The audience could totally have heard this as, “I’m not a Rabbi, I’m a prophet.” And, “I don’t think you’re all worthy of my prophecies.” Notice how Elijah and Elisha were different kinds of prophets: unlike others in the Nevi’im traditions who mostly gave prophecies to Israel, Elijah and Elisha performed mighty, spectacular miracles that saved Israel (for a few moments at least) from outsider incursions. Jesus has associated what he intends to do with the works of Elijah and Elisha, and at the same time, has suggested Nazareth won’t benefit from any of those works.

Now, we can hear Jesus not rejecting Nazareth, but rather Jesus predicting how Nazareth will reject him, and how Jesus even laments this. But putting ourselves in the shoes of regular Nazarenes going to synagogue, especially Nazarenes apparently not accustomed to thinking deeply about the words of Isaiah, we can also hear how they’d be incensed at the implications of what Jesus is teaching, how they take it as one of their own hometown neighbors ripping on them and rejecting them, treating them like as though Sidon and Syria—places outside of covenant Israel—are better than they.

Village elders rage. They “were filled with wrath,” Luke says. And they interrupt their typical worship to deal with this blasphemy, as they see it. Someone probably takes on Jesus directly, accusing him of this or that, and before long, enough people grab Jesus and force him out of the synagogue and a crowd now starts pushing him toward the edge of their town to a spot where they could throw him off a hillside where Jesus might be killed or at least injured. In the very least, this is a public display of exiling a villager, something towns did at the time. It would have carried a kind of formal status that followed such “outcasts,” or shetuqi, people expelled from a local society. Jesus slips out of their midst and avoids being thrown “headlong” down the slope, but quite certainly in the district around Nazareth, he was branded a shetuqi or mamzer, someone no longer welcome in town.

According to the gospels, Jesus makes for the area surrounding Lake Gennesaret where he has at least two associates whom he met back in Bethany-beyond-Jordan: Andrew and Simon.

Capernaum

Mark and Matthew have Jesus next make for Lake Gennesaret while Luke has Jesus leave for Capernaum. From the map, you can see how these locations more or less indicate the same general area. If we assume Jesus took roadways, he probably passed through the biggest city in the area, Sepphoris, and then came through the village Gennesaret before arriving in or around Capernaum. This large village became Jesus’s primary residence for the next stretch of his ministry, and the only place where the gospels suggest he dwelled in his own house. We call it “Capernaum” because of the Latin language and its alphabet replacing the names in their original languages. Just as Jesus did not go by the Latin transliteration of his name (he went by Yeshu‘, and if you care to know the technical ways we know this, I’ll give you this footnote1 to enjoy), the place was Kfar Nahum, meaning, “village of Nahum.”

John has an episode in Bethsaida occur the day after Jesus left Samaria, which, taken in view of the synoptics, seems out of reasonable sequence. This would mean Jesus traversed upper Galilee at least twice (to Bethsaida and back to Nazareth from Bethsaida) before his discourse in the Nazareth synagogue. What seems likely is that Jesus left Nazareth, arrived in Capernaum, and then after some time there, visited other villages along the lakeside that included Bethsaida. If we take this sequence, then the following episodes come next:

Calls of Andrew, Simon, James, and John

Discourse in the Capernaum synagogue

Exorcism in the Capernaum synagogue

Healing of Simon’s mother-in-law

Evening healings of the sick at Simon and Andrew’s house

Solitude

Preaching tour of Galilean towns in synagogues

Calls of Philip and Nathaniel

Healing of a man with leprosy at an unnamed town

Return to Capernaum and healing of a paralyzed man

Call of Levi (also known as Matthew)

Discourse with disciples of John the Baptist

Discourse with Pharisees about the Sabbath among corn fields near Lake Gennesaret

Sabbath healing of a man with a withered hand in the Capernaum synagogue

Withdrawal from towns to lake and mountain plains

Sermon on the Mount/Plain

Events in Capernaum happened in rather quick succession. Jesus came to the lakeside and saw Andrew and Simon casting nets from their boats. Amazingly, we have a fisherman boat from Lake Gennesaret discovered in 1986 that dates to the time of Jesus, and it’s so instructive for how we might imagine this and similar scenes.

This excavated boat is about 8 feet wide and 28 feet long with a depth of about 4 feet, and made of Lebanese cedar planks and oak branches. Archaeological evidence suggests this boat pulled large seine nets to catch fish near the shore and was very likely the largest boat used on Lake Gennesaret. The mast for a sail was removed, leaving archaeologists to speculate whether the boats of the time were designed with removable masts or whether this single boat was retrofitted for a different use at some point in its life. A mosaic in an ancient building depicted this type of boat bearing four oars, requiring a minimum crew of five to operate: four oarsmen and a helmsman.

Only two boats are specified in the Four Gospels: the boat of Simon and Andrew and the boat of James, John, and their father Zebedee. Those same references indicate other crew members, which leave us with an estimated few people per boat on the water at any given voyage. As it happens, an ancient historian, Josephus, described these Galilean boats and said they could hold up to fifteen men apiece, which tracks with what archaeological remains we have.

So, let’s imagine this scene based on these contextual clues: Andrew and Simon operate a fishing concern with at least one boat dragging a seine net near the shore. We have two different versions of events: let’s consider Mark and Matthew’s first. According to them, Jesus calls out to Andrew and Simon, whom he already has met, and says, “Come ye after me” or “Follow me,” and “I will make you fishers of men.” Andrew and Simon leave their boat in the care of other crew members, wade through the shallows, and meet Jesus. They probably converse and get reacquainted. But what Mark and Matthew emphasize is that from that time forward, Andrew and Simon continue with Jesus and never return to their fishing business. Mark and Matthew then have Jesus, Andrew, and Simon go a little farther along the lake until they find Zebedee’s fishing group that included James and John. Here, the brothers are found mending their nets with their father. Jesus calls after James and John, presumably as he did with Andrew and Simon, and the brothers leave the boat to their father Zebedee, and join the three.

Luke’s account has Jesus arrive to two empty boats, one of which is Simon’s, with fisherman cleaning their nets. Jesus enters with Simon into Simon’s boat and tells Simon to “thrust out a little from the land,” a typical distance for where fishermen cast nets in this region. Luke places Jesus in company with other people pressing him to “hear the word of God,” and so Jesus begins preaching to them from the boat. Once finished, Jesus tells Simon to go further and let down their nets for a draw of fish. Simon replies that they had fished all the previous night and caught nothing, but he agrees to let down the nets all the same. Simon and Jesus pull in a massive catch, enough to break the net. They beckon to James, John, and other partners, to take the other boat and help. All told, the catch fills up both boats so much that they can barely stay afloat. At seeing this spectacle and while still in the boat, Simon falls down before Jesus and begs him to depart, saying “for I am a sinful man.” Jesus tells Simon not to fear. “Henceforth, you will catch men.” Once ashore, Simon, James, and John, and presumably others, “forsook all, and followed him.”

The following Sabbath, probably one week after Jesus had read and spoken in the Nazareth synagogue, Jesus and his small group of followers attended the Capernaum synagogue. Mark and Luke simply mention that Jesus taught; what, we don’t know. But his style departed significantly from the scribes, “for his word was with power.”

At some point in the Capernaum synagogue’s liturgy, a man “with an unclean spirit” cried out, “Let us alone; what have we to do with thee, thou Jesus of Nazareth? art thou come to destroy us? I know thee who thou art, the Holy One of God.” Jesus replied, “Hold thy peace, and come out of him.” What followed must have been startling: the unclean spirit tore the man (according to Mark) and threw the man into the middle of the synagogue (according to Luke), but eventually the man was freed of his affliction. This amazed the people so much, they remarked, “What thing is this? What new doctrine is this?” Immediately, Mark says, Jesus’s fame spread abroad “throughout all the region round about Galilee.”

This may have impressed Simon to bring Jesus to his mother-in-law, who, the synoptics say, lay sick of a fever. Jesus either “took her by the hand,” or “touched her hand,” or “stood over her, and rebuked the fever,” but either way, Simon’s mother-in-law arose immediately and “ministered unto them,” a reference in the Greek to her serving them with food. This pericope has the notoriety of being the only place in the gospels where Simon’s wife is mentioned; we don’t know her name or whether she was even alive (Simon may have been a widower).2 Mark has Simon’s mother-in-law living in Simon and Andrew’s house, a common living arrangement at the time.

By that evening, people afflicted with illnesses and “them that were possessed with devils” sought out Jesus and found him at Simon and Andrew’s house. “All the city,” Mark says, “was gathered together at the door.” Jesus “laid his hands on every one of them, and healed them.” Let’s remember the purity culture context that bears on this—Jesus had physically touched a number of people afflicted with disease and illness, in addition to “unclean” spirits. He visibly carried the status under the Torah of “unclean,” and yet we read no mention of him performing purification rituals to become clean again. We do read of the people at the synagogue being astounded at “his authority,” a suggestion that they were beginning to regard Jesus as more than a Rabbi, probably a prophet-level figure at least. Recalling Jesus’s baptism, we know that in Jesus’s case, he had been pronounced “beloved” by God in Heaven ahead of any priestly declaration of ritual purity—and now Jesus conducted himself as no longer submitting to purification laws. He’ll be confronted with this and with Sabbath laws, and Jesus will reply how the human being in need matters far more than any old tradition or even the Torah itself. It’s a revolutionary position to take, one that will further incense those intent on enforcing law and tradition over love and compassion.

The following morning well before dawn, Jesus retired to a solitary place to pray. Simon and others sought after him and eventually found him, letting him know how “All men seek for thee.” (Sidenote: I can’t imagine that burden, being sought after by … everyone. And Jesus had hardly had time to himself just then.) “Let us go into the next towns,” Jesus said, and they all commenced a short preaching tour of other Galilean villages.

By this point, people throughout Galilee had recognized Jesus as a Rabbi/teacher, as a miracle worker, as an exorcist, and as a healer. His reputation on all these fronts would continue to spread far and wide.

Next Time

All of these pericopes are just too wonderfully rich. Skipping over them kills me! We have our next class tomorrow where we’ll begin our discussion of the Sermon on the Mount/Plain, so I don’t know whether I can catch up to it. But I’ll try, even if my summaries stagger a little. Thanks for your patience and interest, and see you in class!

Sources

Lee I. Levine, The Ancient Synagogue, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005).

Shmaryahu Gutman, “The Synagogue at Gamla,” in Ancient Synagogues Revealed, edited by Lee I. Levine (Jerusalem: 1981), 30–34.

Semiticist Benjamin D. Suchard made a study of Jesus’s name and explained it this way (I paraphrase): We know of two ways the name יהושע could have been pronounced at the time of Jesus, one read as yǝhōšūaʿ (Yehoshua) and as yēšūaʿ (Yeshua). The rounded vowel ō became an unrounded ē when appearing before a rounded ū vowel, giving yēšū‘. In other words, a long vowel a‘ got dropped—which is a tricky vowel, one quite difficult for English speakers to pronounce (this video will show you what I mean). The dropping of this a‘ vowel occurs across other transliterations of words and names in other languages of the time. All ancient Greek texts that mention Jesus’s name give iēsous, not iēsouas, indicating the loss of the final “a” in “Yeshua.” Rabbinic texts all refer to Jesus of Nazareth as yēšū with the glottal ū‘ left off. Syriac, the major language of earliest Middle-eastern Christianity, also dropped the final “a” and employed the glottal ū‘. So, taken together, Hebrew, Aramaic, and Syriac at and near the time of Jesus all pronounced the name Yeshua as Yeshu, and usually with a glottal, Yeshu‘. If we’re being precise, we wouldn’t transliterate Jesus’s name into English as “Joshua,” something I’ve heard at times at church; nor should it be transliterated as “Yeshua,” as I was taught in college. We’d steer closer to Yeshu‘ with a nice glottal stop at the end, like this instructor explains well.

Paul asserted that Simon was married in 1 Corinthians 9:5: “Have we not power to lead about a sister, a wife, as well as other apostles, and as the brethren of the Lord, and Cephas [Peter]?” But we still can’t conclude whether she was alive or accompanying Simon when Paul met him. It’s common in Catholic settings for St. Peter to be described as a widower at the time he met Jesus, though this is owed to Catholic tradition more than historical sources.